The Ladder of Citizen Participation

Current events in Rio have left many citizens upset and onlookers confused. The State’s Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program was felt to have so much potential to finally bring security services to underserved parts of the city, and yet, five years on, Rio is steeped in violence and the communities intended to benefit, increasingly victimized by those same police. The Federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) was expected to bring much-needed infrastructure to the city’s favelas, yet the programs launched have been deemed low priority and at times even counter-productive, and so concrete broadly-felt impacts are minimal. Similar concerns can be expressed over the City’s well-written Morar Carioca favela upgrading program, its UPP Social program, and the federal Minha Casa Minha Vida public housing program. While there are many causes and effects involved in the limited success, failures and limitations of each program, what unites them all is the sheer lack of authentic citizen participation.

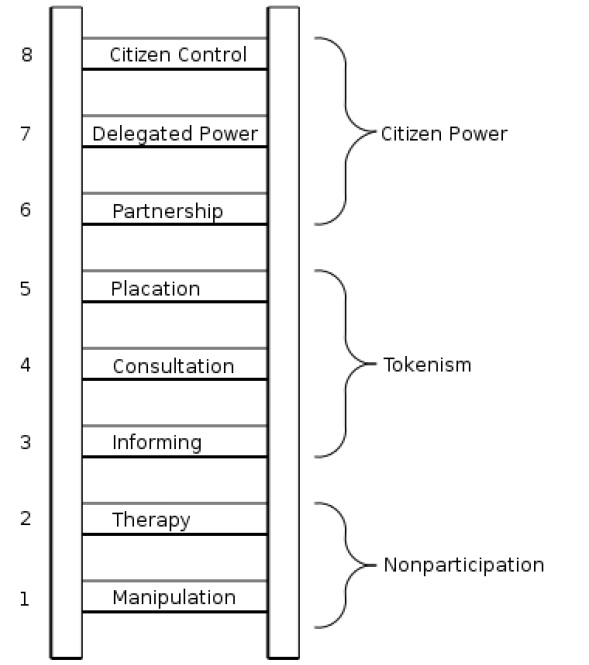

Perhaps the most clear and insightful understanding of the gradations and potential of citizen participation was developed by Sherry Arnstein. In her pioneering 1969 article, A Ladder of Citizen Participation, a mainstay among US city planning educators to this day, she explains the concept using a ladder. Each step of the ladder represents a different level of involvement by the community, and as you go up the ladder, community members are given more power in the process of decision-making. Here we give a brief description of each level of participation, starting at the bottom.

Perhaps the most clear and insightful understanding of the gradations and potential of citizen participation was developed by Sherry Arnstein. In her pioneering 1969 article, A Ladder of Citizen Participation, a mainstay among US city planning educators to this day, she explains the concept using a ladder. Each step of the ladder represents a different level of involvement by the community, and as you go up the ladder, community members are given more power in the process of decision-making. Here we give a brief description of each level of participation, starting at the bottom.

Non-Participation

The first two steps on the ladder of participation are not only considered “Non-Participatory” they are also harmful and disrespectful of citizens.

Manipulation

This level usually includes the appearance of participation, with the creation of community committees or associations. However, these groups are not given any control, and are instead used by those in power to “demonstrate” the use of citizen participation. Often, these meetings end up being more about those in power persuading the participants to think like them, instead of the community members helping the power holders better understand the community. This level of participation has been common historically in Rio’s favelas, particularly during the military regime through the 1980s.

Therapy

There is some overlap between this level and the previous one, manipulation. This level sees the powerlessness of the poor and marginalized as something that can be “cured.” Thus, “participation” ends up exhibiting characteristics of group therapy sessions. With “experts” setting the tone and agenda of these community participation meetings, they often focus on adjusting the values and attitudes of community members so they become more in line with those of broader society.

Tokenism

Within this degree of participation are some good tools and steps toward holistic citizen participation. However, good singular acts are not able to take the place of real community involvement.

Informing

If community involvement stops at being told by officials what is happening, or will happen in the future, little, if any, participation has actually occurred. Some characteristics of this level are that information is given at a very late stage of the process when changes can no longer be made, questions are discouraged, and the information is superficial, irrelevant or incomplete. The PAC program, exemplified by the creation of the cable car in Complexo do Alemão, has typically received this level of participation, calling residents to meetings but not implementing their priorities, instead informing residents of what will happen, and using their signatures of presence at a meeting as approval of the government’s plan. Unfortunately, this is currently the maximum standard of participation in the vast majority of programs in Rio’s favelas. The result is poor quality programs.

If community involvement stops at being told by officials what is happening, or will happen in the future, little, if any, participation has actually occurred. Some characteristics of this level are that information is given at a very late stage of the process when changes can no longer be made, questions are discouraged, and the information is superficial, irrelevant or incomplete. The PAC program, exemplified by the creation of the cable car in Complexo do Alemão, has typically received this level of participation, calling residents to meetings but not implementing their priorities, instead informing residents of what will happen, and using their signatures of presence at a meeting as approval of the government’s plan. Unfortunately, this is currently the maximum standard of participation in the vast majority of programs in Rio’s favelas. The result is poor quality programs.

Consultation

In the United States, the most common form of participation is the survey. For many in poor and marginalized communities, surveys and questionnaires are all too common. They know how many times they have given their opinion and never seen the effects or results from them. When this happens, it creates a distrust between community members and those in power, undermining future attempts at citizen participation. This is the level of participation typical of the UPP Social program, meant to consult with residents in UPP-occupied territories so that social services may follow. The UPP Social has instead turned into a data-gathering agency. The result of consultation or surveying without programs is typically distrust, common among Rio’s favela residents, many of whom have heard many government promises that amount to nothing in the end.

Placation

In attempts to make communities feel heard, the organizing committees and boards will select one or two worthy community members to hold seats on the board. This gives the community voice more access to power holders. Unfortunately, it is just one voice among many others, and can easily be ignored or overruled when final decisions are made. The majority of power still resides outsides the community. Placation may have been seen to be used when, in August of last year, Rio’s Mayor called a small group of representatives of various communities who had attained high visibility in their fight against eviction to the table, to provide a sense that their concerns were being addressed. In the end, these meetings amounted to a press-op and opportunity for the Mayor to retool, promises made shortly thereafter broken.

Citizen Power

At this level actual control of the process is being held, at least in part, by community members themselves. These levels of power often require that citizens be well organized, with neighborhood associations or similar structures in place where residents are active and involved in the daily life of the community.

Partnership

Partnership

Finally, some level of control and power has been given to citizens! This most often looks like joint policy boards, planning committees, and systems to solve conflicts. Power is shared equally between citizen groups and local policy makers. Rio’s favelas, up to 117 years old, have developed over a century almost entirely through self-design, self-regulation, self-build and organic means. Community solutions abound. There is no reason residents are not fully capable of taking this level of control over future development programs, and outcomes will be far superior.

Delegated Power

This level requires that residents have been given more power in the decision-making process than the power holders. This gives citizens a sense of ownership over the state of their community. This often looks like majority presence in decision-making committees and involvement from the beginning of a project. Outsiders are included on committees as well, but ultimately, community members are given the majority of power. An example of this taking place in Rio today is the Minha Casa Minha Vida-Entidades program, a small sub-program within the federal housing program, where resident groups design, build and maintain their own public housing units. A missed opportunity for engaging favela communities in this way is in Vila Autódromo, where the community created its own upgrading plan that recently won the Deutsche Bank award. Unfortunately, the City government has consistently ignored this option, and today the community has been partially demolished.

Citizen Control

This final level allows citizens to be in complete control over their community. They are only below the source of their funds, with a direct connection free of intermediaries. This allows communities to use their resources in exactly the ways they see fit. An example of this approach related to housing that is gaining popularity in the United States and Britain is that of a Community Land Trust.

– Kimberly Farnham recently spent a year an a half in Rio de Janeiro, where she interned with CatComm, while completing her MA in Transformational Urban Leadership from Azusa Pacific University

Published in May 2014